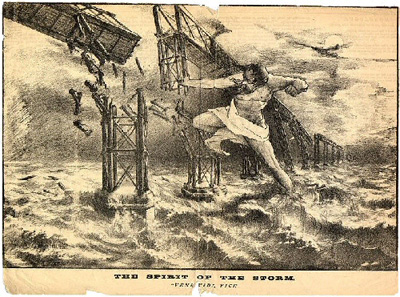

The Tay Bridge was a wonder of the Victorian age when it opened in June 1878: the longest in the world, it earned its creator, Thomas Bouch, a knighthood. “A big bridge for a small city,” said visiting US president Ulysses S Grant. Dundee, on the north side of the Firth of Tay in eastern Scotland, was indeed a small city, and the Fife suburb at the bridge’s southern end was more obscure still.

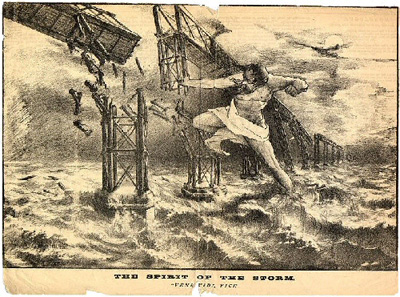

The bridge, however, was a construction to stand among the Victorian landmarks we still admire today – but it didn’t stand for long. A violent storm shook the bridge on 28 December 1879, leading to the collapse of its central section – and plunging a train that had been crossing at the time into the frigid waters of the Tay, along with its 75 doomed passengers.

The disaster provoked an outpouring of national grief and has gone down in history – not least for the infamous commemorative poem by William McGonagall, often feted as Britain’s worst poet:

“Oh! Ill-fated bridge of the silv’ry Tay

I now must conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay

That your central girders would not have given way

At least many sensible men do say

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses

At least many sensible men confesses

For the stronger we our houses build

The less chance we have of being killed.”

Appalling though his poem is, McGonagall is broadly correct about the cause of the disaster. It was evident that the disaster was a mechanical failure, not an Act of God: but who was to blame?

One of those called in to investigate was David Kirkaldy, an engineer who originally hailed from Dundee. Kirkaldy, born in 1820, had dedicated his life to testing the strength of materials used in engineering – initially as a consultant with a Glasgow-based firm and subsequently at his own purpose-built laboratory, situated at what is now the Kirkaldy Museum of Testing at 99 Southwark Street in London – which I visited last Sunday, thanks to a tip-off from the indispensible IanVisits (who blogged about his 2008 trip to the Museum here).

Kirkaldy installed a colossal testing machine in the Southwark premises; it’s still in situ – and still in working order. Nearly fifty feet in length, its 116 tons rest on steel girders that are in turn supported by thick brick pillars (the inevitable question being: who tested the girders to make sure they were up to the job?). It’s a formidable machine that dwarfs the rest of the museum’s motley collection of testing apparatus, including devices for testing the tensile strength of wires, the crush resistance of concrete briquettes and even the durability of parachute webbing.

Why such a huge machine? There was no point testing small samples, since there was no guarantee that the material would be homogeneous. The aim was to test entire components of a bridge or other megastructure – and such huge components could only be accomodated by a huge machine. A photograph in the museum that now stands on the site shows a number of massive bridge spars (that’s unlikely to be the correct term), one of which has sheared cleanly into two pieces – siblings to the spars later used to build Hammersmith Bridge across the Thames.

This was destructive testing, intended to explore the outer limits of what the components could stand. Kirkaldy’s machine applied colossal forces to samples being tested, being rated at up to a thousand pounds per square inch of compression or tension. (It was hydraulically powered using high-pressure water from the London-wide network operated by the London Hydraulic Power Company from 1883 right up until 1977 – sounds like an interesting story in itself.) Not every component could be tested in this way, of course, but it was hoped that sporadic testing would identify dud batches of components.

The committee investigating the Tay Bridge disaster found that the bridge had collapsed because of a combination of design flaws, shoddy maintenance and poor quality construction. The iron columns supporting the highest part of the bridge were weak and variably cast, as were some of the lugs that held together the bridge’s bracing bars. Kirkaldy found that these lugs failed at about 20 tonnes of load, rather than the 60 needed to withstand high winds.

Thomas Bouch, the bridge’s designer, seemed to have paid scant if any attention to the strain that storms would place on the structure, with disastrous results. The inquiry’s damning evidence destroyed his reputation and dashed his hopes of winning the commission to build an even longer bridge across the Firth of Forth, just south of the Firth of Tay. (The Forth Bridge ultimately became the first to be made entirely out of steel, the wonder material of the late Victorian age.) If this were a work of fiction, the affair would would have made Kirkaldy’s name.

But in fact, he seems already to have been well established, having never needed to advertise for business after the initial launch of the Southwark testing house. Repeat business and word of mouth kept it busy not just in Kirkaldy’s own lifetime, but in his son’s and grandson’s too. Part of the key to its success was Kirkaldy’s meticulous record-keeping, so that the results of a test could be verified many years later. He noted the details in ledgers that he kept in a fire-proof safe in his office, where it still stands today – underneath an exquisite diagram of a ship which won Kirkaldy a gold medal for draftsmanship, and opposite his battered armchair and rather stern portrait. The portrait is modern, extrapolated from a contemporary engraving, but the museum volunteers like to think that it captures him rather well.

Kirkaldy was reputedly a dour and obstinate man, the kind of person who brooked little dissent and deferred to nobody. (“Take away his beard,” one museum volunteer told us, “and you pretty much have Gordon Brown.”) Perhaps his attitude was defensible; the lab’s motto – inscribed in stone above its entrance – was “Facts Not Opinions”, and Kirkaldy seems to have stuck to it pretty rigorously. On the upper floor of the testing house, he kept a “Museum of Fractures”, which from surviving photographs would seem to have been an exhaustive collection of broken pieces of metal. One suspects that those who accepted an invitation to view it might soon have regretted doing so.

Kirkaldy’s brute-force approach to materials science might seem crude, and his meticulous approach almost obsessive. But the painstaking work that he and his peers did laid the foundations for modern materials science and mechanical engineering. Unproven new materials, such as steel, could not have become ubiquitous without exhaustive tests to demonstrate their properties and ensure their suitability. As time went on and quality control improved, it became possible to test smaller samples, ultimately rendering Kirkaldy’s giant machine redundant – although not until well into the twentieth century.

And all this means that there were no excuses for those who failed to take the proper precautions when designing vast new engineering projects, like Thomas Bouch. There’s a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s 1935 poem “The Hymn of Breaking Strain” in the Museum:

The careful text-books measure

(Let all who build beware!)

The load, the shock, the pressure

Material can bear.

So, when the buckled girder

Lets down the grinding span,

The blame of loss, or murder,

Is laid upon the man.

Not of the Stuff – the Man!

This must have made Kirkaldy enemies – perhaps that’s why his obituary supposedly terms him “the best-hated man in England”. But the travelling public had ample reason to be grateful to him. Over the next few decades, heavy engineering became less of an art and more of a science: because it was based on facts, not opinions.